Institute Announcements

In The News: URMC utilizes motion capture technology to study brain, how it ages

Wednesday, December 26, 2018

The following is an excerpt from an article by Norma Holland that originally appeared on WHAM 13:

Rochester, N.Y. -- From Hollywood to Healthcare: Technology used to make movies is being used at the University of Rochester Medical Center to help scientists understand the brain and how it ages.

What researchers learn could help predict a person's risk of developing Alzheimer's disease.

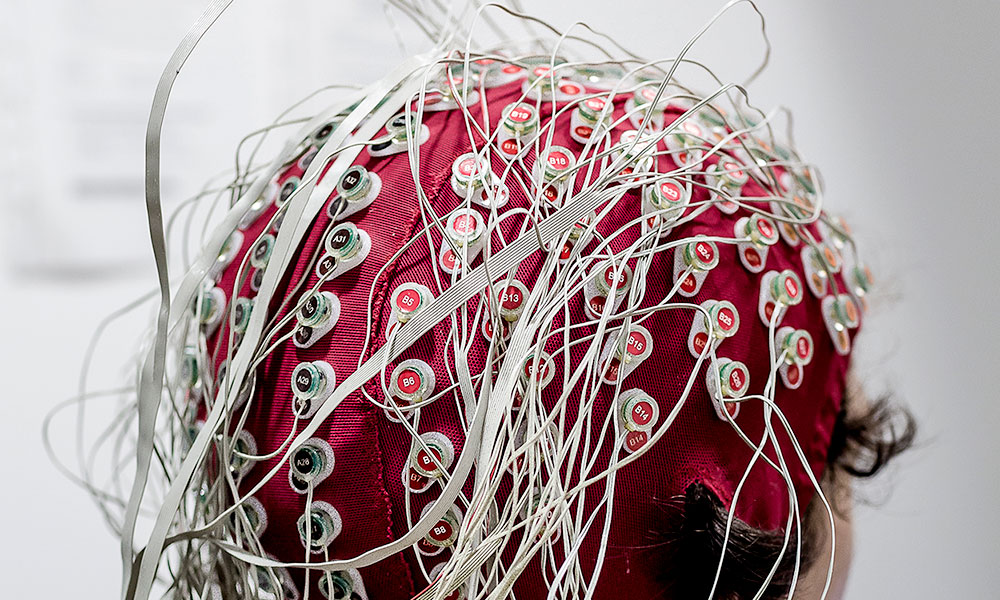

13WHAM watched researchers in the Mobile Brain Body Imaging -- or MoBi -- Lab attach wires to a cap covered in electrodes. The cap picks up the brain wave activity of a volunteer, while infrared cameras surrounding him pick up how his body moves on a treadmill.

This lab is one of 12 around the world combining motion capture technology with brain scans used in real time.

"What we're saying is: Let's get people up, let's get them in a walking situation where they're solving a task, where we can kind of stress them a bit, and then we can ask, 'How's the brain working under duress?' explained Dr. John Foxe, director of the Del Monte Institute for Neuroscience. "And that gives us a window into function, maybe like a neural stress test, akin to the cardiac stress test."

Armed with that information, doctors hope to one day be able to predict a person's dementia risk a decade before symptoms show up. It can also help give us clues about a person's risk of falling as they get older.

Study Confirms Central Role of Brain’s Support Cells in Huntington’s, Points to New Therapies

Thursday, December 13, 2018

New research gives scientists a clearer picture of what is happening in the brains of people with Huntington's disease and lays out a potential path for treatment. The study, which appears today in the journal Cell Stem Cell, shows that support cells in the brain are key contributors to the disease.

"Huntington's is a complex disease that is characterized by the loss of multiple cell populations in the brain," said neurologist Steve Goldman, M.D., Ph.D., the lead author of the study and the co-director of the Center for Translational Neuromedicine at the University of Rochester Medical Center (URMC). "These new findings help pinpoint how the genetic flaw in Huntington's gives rise to glial cell dysfunction, which impairs the development and role of these cells, and ultimately the survival of neurons. While it has long been known that neuronal loss is responsible for the progressive behavioral, cognitive, and motor deterioration of the disease, these findings suggest that it's glial dysfunction which is actually driving much of this process."

Huntington's is a hereditary and fatal neurodegenerative disease characterized by the loss of medium spiny neurons, a nerve cell in the brain that plays a critical role in motor control. As the disease progresses over time and more of these cells die, the result is involuntary movements, problems with coordination, and cognitive decline, depression, and often psychosis. There is currently no way to slow or modify the progression of this disease.

In The News: How well can you walk, think at same time? URMC uses ability to predict Alzheimer's risk

Monday, November 19, 2018

The following is an excerpt from an article by Patti Singer that originally appeared in the Rochester Democrat & Chronicle.

I'm giving my brain a stress test.

I'm walking on a treadmill in a dark room where every second or so, two sets of lines flash on the wall-sized screen in front of me. I have a second to decide which set is rotated farther clockwise. If it's the left one, I push the button I'm holding in my left hand. If it's the right one, I push the button in my right hand.

"Jeez," I mutter after getting it wrong, again.

Turns out, walking while thinking isn't as easy as it looks.

Neuroscientists at the University of Rochester Medical Center want to find out whether older adults who struggle to do both at once might be at risk for Alzheimer's disease.

The researchers recently started using motion capture technology — what's used to get the realistic movements in sports video games — and recording brain activity to see at what point communication from the brain to the muscles breaks down. They want to know what that means for someone still trying to function in the everyday world.

The technology can be applied to autism, traumatic brain injury, concussion, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder or Parkinson's disease. Right now, the focus is Alzheimer's, which is the sixth leading cause of death nationwide. According to a 2017 report from the state Department of Health, nearly 400,000 New Yorkers had Alzheimer's disease. The figure was expected to be 460,000 by 2025. There is no cure for the disease, but the goal of researchers is to predict who might be at risk so that treatments start earlier and slow the progression of Alzheimer's.

Researchers in the Ernest J. Del Monte Institute for Neuroscience are enrolling three groups of older adults — those who are healthy, those with cognitive impairment and those with Alzheimer's — to determine whether they can predict someone's risk of developing the disease. At some point, the technology could be used to track the effectiveness of treatment.

Save the Date: Poster Session & Happy Hour

Monday, November 19, 2018

The Rochester Chapter of the Society for Neuroscience is hosting a Poster Session and Happy Hour with prizes for the best posters. Students and Postdoctoral fellows may register any poster that you have presented in the past year (SfN Meeting, VSS, IMRF, ARO or other recent meetings).

To register your poster please email your name, poster title, department affiliation and status (graduate student, undergraduate, postdoctoral fellow) to Tori D'Agostino: Victoria_DAgostino@urmc.rochester.edu

Neuroscience Poster Session and Happy Hour

LeChase Hall, Medical Center

3:00 -- 6:00 p.m. Friday, November 30, 2018

Maiken Nedergaard Recognized for Groundbreaking Research on Glymphatic System

Tuesday, November 13, 2018

Maiken Nedergaard, M.D., D.M.Sc., has been awarded the with the 2018 Eric K. Fernstrom Foundation Grand Nordic Prize for her work that led to the discovery of the brain's unique waste removal system and its role in a number of neurological disorders. Nedergaard maintains labs at the Medical Center and the University of Copenhagen.

In 2012, Nedergaard's lab was the first to reveal the brain's unique process of removing waste, dubbed the glymphatic system, which consists of a plumbing system that piggybacks on the brain's blood vessels and pumps cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) through the brain's tissue, flushing away waste.

Nedergaard's lab has since gone on to show that the glymphatic system works primarily while we sleep, could be a key player in diseases like Alzheimer's, is disrupted after traumatic brain injury, may be enhanced by moderate alcohol consumption, and could be harnessed as a new way to deliver drugs to the brain.

The Eric K. Fernstrom Foundation annually awards the Grand Nordic Prize to a medical research from one of the Nordic Countries. The award was announced during a ceremony on November 7 at Lund University in Sweden.

Neuroscience Grad Student Named to Equity and Inclusion Search Committee

Tuesday, November 6, 2018

Monique Mendes, Neuroscience PhD Candidate, has been named to the search committee for the University of Rochester's first vice president for equity and inclusion. Monique was peer-nominated and chosen to join the committee which includes faculty, staff and students from across the University and will be led by University President Richard Feldman. She is one of just three students who were selected to participate. Congratulations, Monique!

Monique Mendes, Neuroscience PhD Candidate, has been named to the search committee for the University of Rochester's first vice president for equity and inclusion. Monique was peer-nominated and chosen to join the committee which includes faculty, staff and students from across the University and will be led by University President Richard Feldman. She is one of just three students who were selected to participate. Congratulations, Monique!

Mock Receives National Recognition for Leadership in Inclusive Higher Education

Tuesday, October 30, 2018

In a room packed with hundreds of colleagues, policymakers, and families at the 2018 State of the Art (SOTA) Conference on Postsecondary Education and Individuals with Intellectual Disabilities in Syracuse, N.Y., Martha Mock was presented the Leadership in Inclusive Higher Education Award on October 10. The award recognizes an administrator, program director, or staff member with a higher education institution who epitomizes leadership in the postsecondary field.

In a room packed with hundreds of colleagues, policymakers, and families at the 2018 State of the Art (SOTA) Conference on Postsecondary Education and Individuals with Intellectual Disabilities in Syracuse, N.Y., Martha Mock was presented the Leadership in Inclusive Higher Education Award on October 10. The award recognizes an administrator, program director, or staff member with a higher education institution who epitomizes leadership in the postsecondary field.

Cindi May, a 2018 SOTA Conference advisory board member and a professor from the College of Charleston, presented the award with a powerful speech outlining Mock's leadership in higher education.

"Martha's passion for inclusive higher education for students with intellectual disabilities is contagious, and her work for the past decade has helped make tremendous gains in our still-new field," May said. "Her dedicated leadership has directly resulted in the establishment and growth of opportunities in the state of New York and across the country. She employs an approach that emphasizes empowerment of people with intellectual disabilities, strong community collaborations, and effective advocacy at all levels."

Mock is a clinical professor at the University of Rochester's Warner School of Education, where she serves as director of both the early childhood and inclusion/special education teacher preparation programs and the Center on Disability and Education. Mock's career in inclusion, transition and education spans more than two decades, including her time as a teacher, professor and advocate working alongside and on behalf of individuals with disabilities and their families. For more than a decade, she has worked to change the landscape of educational opportunities for transition-age students with intellectual and developmental disabilities. In doing so, she has impacted practice, policy, and outcomes for students across the nation.

New Research Initiative to Focus on Cerebrovascular Diseases

Monday, October 29, 2018

A multidisciplinary group of clinical and bench researchers has been formed at the University of Rochester Medical Center (URMC) to study cerebrovascular disease. The Cerebrovascular and Neurocognitive Research Group (CNRG), which consists of faculty from Neurology, Neurosurgery, Electrical and Computer Engineering, Microbiology and Immunology, and Vascular Biology will leverage advanced brain imaging technologies to investigate a number of diseases, including stroke, cerebral small vessel disease (CSVD), and vascular dementia.

A multidisciplinary group of clinical and bench researchers has been formed at the University of Rochester Medical Center (URMC) to study cerebrovascular disease. The Cerebrovascular and Neurocognitive Research Group (CNRG), which consists of faculty from Neurology, Neurosurgery, Electrical and Computer Engineering, Microbiology and Immunology, and Vascular Biology will leverage advanced brain imaging technologies to investigate a number of diseases, including stroke, cerebral small vessel disease (CSVD), and vascular dementia.

These efforts are being supported in part by a new $2.7 million grant from the National Institute of Mental Health, to study how chronic inflammation drives cerebrovascular disease and disrupts the structure and connections between different parts of the brain.

RCBI is Now UR CABIN

Friday, October 26, 2018

The former Rochester Center for Brain Imaging has been renamed the University of Rochester Center for Advanced Brain Imaging & Neurophysiology (UR CABIN). UR CABIN is a research facility offering a state-of-the-art 3 Tesla magnet for the purpose of conducting investigations using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to researchers from the University of Rochester Medical Center and River Campus, neighboring institutions, and the science and technology industries. UR CABIN is also home to several high-density electrophysiology recording suites, as well as the Mobile Brain/Body Imaging system, or MoBI, which combines virtual reality, brain monitoring, and Hollywood-inspired motion capture technology, allowing researchers to track and study the areas of the brain being activated when walking or performing tasks. UR CABIN is located in the Medical Center Annex building at 430 Elmwood Avenue. For more information, please reach out to Kathleen Jensen.

Study Points to New Method to Deliver Drugs to the Brain

Thursday, October 18, 2018

Researchers at the University of Rochester Medical Center (URMC) have discovered a potentially new approach to deliver therapeutics more effectively to the brain. The research could have implications for the treatment of a wide range of diseases, including Alzheimer's, Parkinson's, ALS, and brain cancer.

"Improving the delivery of drugs to the central nervous system is a considerable clinical challenge," said Maiken Nedergaard M.D., D.M.Sc., co-director of the University of Rochester Medical Center (URMC) Center for Translational Neuromedicine and lead author of the article which appears today in the journal JCI Insight. "The findings of this study demonstrate that the brain's waste removal system could be harnessed to transport drugs quickly and efficiently into the brain."

Many promising therapies for diseases of the central nervous system have failed in clinical trials because of the difficulty in getting enough of the drugs into the brain to be effective. This is because the brain maintains its own closed environment that is protected by a complex system of molecular gateways -- called the blood-brain barrier -- that tightly control what can enter and exit the brain.

New Neuroscience Grant Awards – August 2018

Tuesday, October 16, 2018

Congratulations to the following faculty members who received funding for various neuroscience research projects in August!

Investigator:Harris A Gelbard

Project Title: URMC-099 In in vivo AAV-hSYN and in vitro Dopaminergic Neuron Models

Sponsor: The Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson's Disease

Investigator: Cornelia Kamp

Project Title: Clinical Coordinating Center Network of Excellence in Neuroscience Clinical Trial

Sponsor: Massachusetts General Hospital

Investigator:Anne E Luebke

Project Title: NeuroDataRR. Collaborative Research: Testing the relationship between musical training and enhanced neural coding and perception in noise

Sponsor: National Science Foundation

Investigator:Margot Mayer-Proschel

Project Title: Gestational Iron Deficiency disrupts neural patterning in the embryo

Sponsor: Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development

Investigator:Thomas G O'Connor

Project Title: Pre- and Post-Natal Exposure Periods for Child Health: Common Risks and Shared Mechanisms

Sponsor: NIH Office of the Director

Investigator:Krishnan Padmanabhan

Project Title: CAREER: Investigating how internal states, learning and memory shape olfactory coding

Sponsor: National Science Foundation

Investigator: Christoph Proschel

Project Title: iPSC-derived astrocytes to model Vanishing White Matter Disease

Sponsor: National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke

Investigator:Marc H Schieber

Project Title: Injecting instructions using intracortical microstimulation in association cortex

Sponsor: National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke

Investigator: Marc H Schieber

Project Title: Observation of Performance

Sponsor: National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke

Study Points to Possible New Therapy for Hearing Loss

Monday, October 15, 2018

Researchers have taken an important step toward what may become a new approach to restore the hearing loss. In a new study, out today in the European Journal of Neuroscience, scientists have been able to regrow the sensory hair cells found in the cochlea -- a part of the inner ear -- that converts sound vibrations into electrical signals and can be permanently lost due to age or noise damage.

Researchers have taken an important step toward what may become a new approach to restore the hearing loss. In a new study, out today in the European Journal of Neuroscience, scientists have been able to regrow the sensory hair cells found in the cochlea -- a part of the inner ear -- that converts sound vibrations into electrical signals and can be permanently lost due to age or noise damage.

Hearing impairment has long been accepted as a fact of life for the aging population -- an estimated 30 million Americans suffer from some degree of hearing loss. However, scientists have long observed that other animals -- namely birds, frogs, and fish -- have been shown to have the ability to regenerate lost sensory hair cells.

"It's funny, but mammals are the oddballs in the animal kingdom when it comes to cochlear regeneration," said Jingyuan Zhang, Ph.D., with the University of Rochester Medical Center (URMC) Department of Neuroscience and first author of the study. "We're the only vertebrates that can't do it."

Research conducted in the lab of Patricia White, Ph.D., in 2012 identified a family of receptors -- called epidermal growth factor (EGF) -- responsible for activating support cells in the auditory organs of birds. When triggered, these cells proliferate and foster the generation of new sensory hair cells. She speculated that this signaling pathway could potentially be manipulated to produce a similar result in mammals. White is a research associate professor in the University of Rochester Medical Center (URMC) Del Monte Institute for Neuroscience and lead author of the current study.

URMC Joins Network Dedicated to Improving Care for Spinal Muscular Atrophy

Monday, October 15, 2018

The University of Rochester Medical Center (URMC) has been selected as one of the first four institutions in the U.S. to participate in the SMA Care Center Network. The network is being created as new treatments and approaches to care are transforming how spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) is treated.

Professor Carney will speak at Rochester Science Cafe

Wednesday, October 10, 2018

Professor Laurel Carney will be speaking at the Rochester Science Cafe at the Pittsford Barnes & Noble on Tuesday, October 23 at 7pm. She will be speaking in the community room on the topic, "'What?' How Hearing Loss Affects Speech Perception." Science Cafes are interactive events involving face-to-face conversations with leading scientists about relevant current topics. For more information, visit sciencecaferochester.blogspot.com.

Professors Anne Luebke and Ross Maddox receive NSF award

Tuesday, October 2, 2018

BME Professors Anne Luebke and Ross Maddox along with Co-PI Elizabeth Marvin (Eastman School of Music) have received an award from the National Science Foundation for their project, "NeuroDataRR. Collaborative Research: Testing the relationship between musical training and enhanced neural coding and perception in noise." This is a collaborative effort involving several universities: University of Minnesota (Dr. Andrew Oxenham, Lead PI), Purdue University, Carnegie Mellon University, Boston University, University of Western Ontario, and the University of Rochester.

This project will determine whether formal musical training is associated with enhanced neural processing and perception of sounds, including speech in noisy backgrounds. Music forms an important part of the lives of millions of people around the world, and it is one of the few universals shared by all known human cultures. Yet its utility and potential evolutionary advantages remain a mystery. This project will test the hypothesis that early musical exposure has benefits that extend beyond music to critical aspects of human communication, such as speech perception in noise. In addition, this project will test whether early musical training is associated with less severe effects of ageing on the ability to understand speech in noisy backgrounds. Degraded ability to understand speech in noise is a common complaint among older listeners, and one that can have a profound impact on quality of life, as has been shown by the associations between hearing loss, social isolation, and more rapid cognitive and health declines. If formal musical training is shown to be associated with improved perception and speech communication in later life, the outcomes could have a potentially major impact on many aspects of public and educational policy.

UR Medicine Unveils Upstate New York’s First Mobile Stroke Unit

Thursday, September 27, 2018

Next month, UR Medicine will begin operation of a Mobile Stroke Unit (MSU), a high-tech 'emergency room on wheels' that is designed to provide life-saving care to stroke victims. The $1 million unit will be operated in partnership with AMR as a community resource and represents a significant step forward for stroke care in the Rochester region.

Next month, UR Medicine will begin operation of a Mobile Stroke Unit (MSU), a high-tech 'emergency room on wheels' that is designed to provide life-saving care to stroke victims. The $1 million unit will be operated in partnership with AMR as a community resource and represents a significant step forward for stroke care in the Rochester region.

While the MSU resembles an ambulance on the outside, inside it contains highly specialized staff, equipment, and medications used to diagnose and treat strokes. The unit is equipped with a portable CT scanner that is capable of imaging the patient's brain to detect the type of stroke they are experiencing. The scans and results from a mobile lab on the unit are wirelessly transmitted to UR Medicine stroke specialists at Strong Memorial Hospital, who will consult with the on board EMS staff via telemedicine and decide if they can begin treatment immediately on scene.

If it is determined that the patient is experiencing an ischemic stroke -- which account for approximately 90 percent of all strokes -- the MSU team can administer the drug tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) to attempt to break up the clot in the patient's brain. While en route to the hospital, UR Medicine specialists will continue to remotely monitor and assess the patient's symptoms.

"The UR Medicine Mobile Stroke Unit essentially brings the hospital to the patient," said Tarun Bhalla, M.D., Ph.D., Chief of Stroke and Cerebrovascular Surgery the UR Medicine Comprehensive Stroke Center. "This unit will improve care and outcomes by shortening the gap between diagnosis and treatment and enable us to initiate care before the patient reaches the hospital."

Common Painkiller Not Effective for Traumatic Nerve Injury

Monday, September 24, 2018

A new study out today in the Journal of Neurology finds that pregabalin is not effective in controlling the chronic pain that sometimes develops following traumatic nerve injury. The results of the international study, which was driven by an effort to identify effective non-opioid pain medications, did show potential in relieving in pain that sometimes lingers after surgery.

"The unrelenting burning or stabbing symptoms due to nerve trauma are a leading reason why people seek treatment for chronic pain after a fall, car accident, or surgery," said John Markman, M.D., director of the Translational Pain Research Program in the University of Rochester Department of Neurosurgery and lead author of the study. "While these finding show that pregabalin is not effective in controlling the long-term pain for traumatic injury, it may provide relief for patients experience post-surgical pain."

Pregabalin, which is marketed by Pfizer under the name Lyrica, is approved to treat chronic pain associated with shingles, spinal cord injury, fibromyalgia, and diabetic peripheral neuropathy. However, it is also commonly prescribed as an "off label" treatment for chronic nerve injury syndromes that occur after motor vehicle accidents, falls, sports injuries, knee or hip replacement and surgeries such as hernia repair or mastectomy.

Krishnan Padmanabhan 2018 CAREER Recipient

Friday, September 14, 2018

Krishnan Padmanabhan was among the eight University of Rochester researchers are among the latest recipients of the National Science Foundation's most prestigious recognition for junior faculty members: the Faculty Early Career Development (CAREER) award.

Krishnan will use neural tracers, ontogenetic technology, and electrical recordings in the brain to understand how internal state, learning, and memory influence the neurons that shape the perception of smell. "The same cookie may smell and taste differently, depending on our emotional state, our experiences, and our memories," he says. By interrogating a recently characterized connection between the hippocampus and the olfactory bulb, he aims to understand how perception is reshaped by experience.

Neuroscience Graduate Program Student Receives Award for SfN Trainee Professional Development

Tuesday, September 11, 2018

Emily Warner was recently selected to receive a 2018 Trainee Professional Development Award (TPDA) from the Society for Neuroscience. These are highly competitive awards and it is a great achievement for Emily.

Emily Warner was recently selected to receive a 2018 Trainee Professional Development Award (TPDA) from the Society for Neuroscience. These are highly competitive awards and it is a great achievement for Emily.

The award comes with a complementary registration to the conference in San Diego and a monetary award of $1000. Emily will present a poster at a poster session for other recipients and will be able to attend several Professional Development Workshops while at the conference.

Congratulations Emily!

Drug Shows Promise in Slowing Multiple Sclerosis

Wednesday, September 5, 2018

Research appearing in the New England Journal of Medicine could herald a new treatment approach for individuals with multiple sclerosis (MS) if confirmed in future studies. The results of a clinical trial, which involved researchers from the University of Rochester Medical Center (URMC), showed that the drug ibudilast slowed the brain shrinkage associated with progressive forms of the disease.

"These results indicate that ibudilast may be effective in protecting the central nervous system and slowing the damage to the brain that is caused by MS," said URMC neurologist Andrew Goodman, M.D., a co-author of the study who served on the national steering committee for the Phase II clinical trial, dubbed SPRINT-MS. "While more clinical research is necessary, the trial's results are encouraging and point towards a potential new type of therapy to help people with progressive MS."

MS is a neurological disorder in which the body's own immune system attacks myelin, the fatty tissue that insulates the nerve fibers in the brain and spinal cord. These attacks are caused by inflammation which damages myelin, disrupting communication between nerve cells and leading to cognitive impairment, muscle weakness, and problems with movement, balance, sensation, and vision. MS usually presents with a relapsing-remitting course, in which symptoms occur then disappear for weeks or months and then may reappear, or primary and secondary progressive courses, which are marked by a gradual decline in function.

Researchers Harness Virtual Reality, Motion Capture to Study Neurological Disorders

Wednesday, September 5, 2018

Neuroscientists at the University of Rochester Medical Center (URMC) have a powerful new state-of-the-art tool at their disposal to study diseases like Autism, Alzheimer’s, and traumatic brain injury. The Mobile Brain/Body Imaging system, or MoBI, combines virtual reality, brain monitoring, and Hollywood-inspired motion capture technology, enabling researchers to study the movement difficulties that often accompany neurological disorders and why our brains sometimes struggle while multitasking.

“Many studies of brain activity occur in controlled environments where study subjects are sitting in a sound proof room staring at a computer screen,” said John Foxe, Ph.D., director of the URMC Del Monte Institute for Neuroscience. “The MoBI system allows us to get people walking, using their senses, and solving the types of tasks you face every day, all the while measuring brain activity and tracking how the processes associated with cognition and movement interact.”

The MoBI platform – which is located in the Del Monte Institute’s Cognitive Neurophysiology Lab – brings together several high tech systems. Using the same technology that is employed by movie studios to produce CGI special effects, study participants wear a black body suite that is fitted with reflective markers. Participants are then asked to walk on a treadmill or manipulate objects at a table in a room fitted out with 16 high speed cameras that record the position of the markers with millimeter precision. This data is mapped to a computer generated 3D model that tracks movement.

Professor recognized for transforming understanding of human language

Tuesday, September 4, 2018

Michael K. Tanenhaus, a longtime professor of brain and cognitive sciences, is being recognized for work that has "transformed our understanding of human language and its relation to perception, action, and communication" by the premier academic society in his field.

Michael K. Tanenhaus, a longtime professor of brain and cognitive sciences, is being recognized for work that has "transformed our understanding of human language and its relation to perception, action, and communication" by the premier academic society in his field.

At the annual meeting of the Cognitive Sciences Society this summer, Tanenhaus was formally awarded the David E. Rumelhart Prize from the Cognitive Science Society and the Robert J. Glushko and Pamela Samuelson Foundation. The prize is the highest honor given by the Cognitive Science Society to recognize a "significant contribution to the theoretical foundations of human cognition."

Tanenhaus, the Beverly Petterson Bishop and Charles W. Bishop Professor of Brain and Cognitive Sciences, says he's humbled to join a list of honorees that include "giants in cognitive science from multiple disciplines, including computer science, linguistics, and psychology."

Over the course of his 40-year career, Tanenhaus has focused his research on the mechanisms underlying language comprehension. He is best known as the creator of the Visual World Paradigm, which uses eye movements to study the mechanisms behind speech and language comprehension. According to the society, the paradigm has been widely adopted for studying language development and disorders.

Dr. Mayer-Pröschel to Research the Role of Iron Deficiency in the Developing Brain with a $2 Million Grant

Wednesday, August 29, 2018

Dr. Margot Mayer-Pröschel, Associate Professor in the Department of Biomedical Genetics, with a secondary appointment in the Department of Neuroscience, has received a $2 million, five-year grant to study the impact of gestational iron deficiency (GID) on the development of the brain.

Iron deficiency is still the most prevalent nutritional deficiency in the world. Optimal maternal iron stores during pregnancy are essential for providing adequate iron to the fetal brain. However, many women have insufficient iron reserves to optimally supply the fetus. This is a potentially serious problem as children born to gestational iron deficient (GID) mothers have a higher probability of developing autism, attention deficient syndrome and other cognitive impairments.

A major step towards understanding GID, and potentially preventing multiple types of impairment in children, is to conduct controlled mechanistic and cellular studies in animal models where variable factors can be controlled. Using this approach, the Mayer-Pröschel lab found that low iron supply during pregnancy can cause defects in fetal brain development resulting in a disability to generate appropriate reservoirs of cells that are needed later in life to establish balanced brain activity. This defect persists even if iron supplements are started at birth. This work using a mouse model of GID will provide a detailed understanding of the detrimental effects on child development and may point towards new strategies by which the defects can be normalized or prevented.

The grant, titled Gestational Iron Deficiency disrupts neural patterning in the embryo is funded by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development (NICHD), part of National Institutes of Health.

Richard Barbano Co-Authors New Guideline for Managing Consciousness Disorders

Thursday, August 16, 2018

A new practice guideline update for the diagnosis and ongoing medical and rehabilitative care of individuals in a vegetative or minimally conscious state has a result of a brain injury have been published by the American Academy of Neurology, the American Congress of Rehabilitation Medicine, and the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research.

URMC neurologist Richard Barbano, M.D., Ph.D., was part of a team of physicians and researchers who prepared the new guideline, which appears in the journal Neurology.

The experts carefully reviewed all of the available scientific studies on diagnosing, predicting health outcomes, and caring for people with disorder of consciousness, focusing on evidence for people with prolonged disorders of consciousness -- those cases lasting 28 days or longer.

The guideline recommends that a clinician trained in the management of disorder of consciousness, such as a neurologist or brain injury rehabilitation specialists, should do a careful evaluation and the evaluation should be repeated several times early in recovery.

Additional findings include:

- The outcomes for patients with prolonged disorder of consciousness differ greatly. It is estimated that one in five people with severe brain injury from trauma will recover to the point where they can live at home and care for themselves without assistance.

- There is moderate evidence that patients with a brain injury from trauma will fare better in terms of recovery than a person with a brain injury from another cause.

- Very few treatments for disorder of consciousness have been carefully studied. However, moderate evidence shows that the drug amantadine can hasten recovery in patients with disorder of consciousness after a traumatic brain injury when used within one to four months after the injury.

Committed to Memory: How does memory shape our sense of who we are?

Wednesday, August 15, 2018

What do we remember? And how do we forget? Complicated questions, their manifold answers are pursued by scholars, scientists, and artists.

"Memory studies are a burgeoning area of humanistic inquiry that encompasses multiple fields," says Joan Shelley Rubin, the Dexter Perkins Professor of History and the Ani and Mark Gabrellian Director of the Humanities Center. The center chose memory and forgetting as the annual theme for its programs over the past year, with guest lectures, workshops, art exhibitions, and internal and external faculty research fellows in residence.

"It seemed an excellent way to achieve the Humanities Center's goal of fostering collaboration and interdisciplinary exchange. Individual memories are such an integral part of our identities as people, and collective memories—entangled as they are with history and culture—shape the politics, society, and artistic expression of the present," Rubin says.

Visit the site to read samples of how Rochester researchers are currently working with memory, including a section by John Foxe, Director of Del Monte Institute for Neuroscience."

Tristram Smith, Pioneer in Autism Research, Dies at 57

Thursday, August 9, 2018

Tristram Smith, Ph.D., whose research on behavioral interventions changed the landscape of care for children with autism spectrum disorders (ASD), died after suffering a heart attack on Monday morning. He was 57.

Tristram Smith, Ph.D., whose research on behavioral interventions changed the landscape of care for children with autism spectrum disorders (ASD), died after suffering a heart attack on Monday morning. He was 57.

At the time of his death, Smith was serving as the Haggerty-Friedman Professor in Developmental/Behavioral Pediatric Research at the University of Rochester Medical Center (URMC), where he had worked since joining faculty in 2000.

His research in the late '80s and early '90s, conducted alongside the late O. Ivar Lovaas, Ph.D., showed that many children with ASD could be successfully treated with behavior-based interventions, which allowed some to catch up to their peers in school. The work helped move treatment of children with ASD away from psychotherapy — which had been used with nominal effectiveness for decades — and toward applied-behavior based models. The sea change in treatment paved the way for ASD screenings in schools and pediatricians' offices and led to numerous additional studies on behavior-based interventions.

New blood test for brain injury at URMC

Thursday, July 26, 2018

Researchers at the University of Rochester Medical Center have a new, FDA-approved test to detect brain injuries, according to a study published Wednesday in the journal The Lancet Neurology.

The new test looks for certain telltale proteins that enter the bloodstream after a traumatic brain injury. Jeffrey Bazarian, a professor of emergency medicine and neurology at URMC and a lead author of the study, said the blood test promises to reduce the need for CT scans of the head, which he said have been the "gold standard" of brain injury detection.

Those scans are one of the few ways doctors have of seeing inside the head, Bazarian said. An opening in the blood-brain barrier, which happens as a result of a traumatic injury, offers another. "It's usually closed," Bazarian said of the barrier, "but a blow opens it up, which is lucky for us because it allows us to have a brief window into what's happening in the brain."

NIH Extends URMC’s Role in Network to Advance Neurological Care

Thursday, July 26, 2018

National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) has extended the University of Rochester Medical Center's (URMC) membership in the Network for Excellence in Neuroscience Clinical Trials, or NeuroNEXT, which was created to accelerate clinical research involving new treatments for neurological disorders. The $1.5 million grant will provide patients in the region access to cutting-edge experimental therapies and continue the Medical Center's key role in helping bring new drugs to market.

"Neurological diseases are some of the most challenging in all of medicine and the process of translating promising discoveries into new treatments requires building partnerships across many institutions in order to create the infrastructure necessary to recruit patients and run multi-site clinical trials," said Robert Holloway, M.D., M.P.H., chair of the URMC Department of Neurology and principal investigator of the URMC NeuroNEXT site. "The Medical Center has a long history in the field of experimental therapeutics and we are proud to be a part of NeuroNEXT and to support efforts that will make clinical research better, faster, and more efficient in the quest to aid patients and families affected by neurological disease."

In 2011, URMC was one of the original 25 institutions selected to participate in NeuroNEXT. The network was created to streamline the operations of neuroscience clinical trials and help increase the number of new treatments that get into clinical practice. The program is designed to encourage collaborations between academic centers, disease foundations, and industry.

Over the last five years, URMC has been involved in NeuroNEXT studies involving the testing of new drugs for myasthenia gravis, multiple sclerosis, Huntington's disease, stroke, brain cancer, and neuropathy. "We could not have accomplished this without the phenomenal talent and dedication of our faculty, study coordinators, and research teams." said Erika Augustine, M.D., M.S., co-Investigator on the grant.

"One of the advantages of NeuroNEXT, and something that makes it unique, is the network's ability to quickly mobilize a group of specialists from a certain disease area to initiate a clinical study when opportunities emerge for trials," said Robin Conwit, M.D., program director at NINDS. "The structure of NeuroNEXT, with its broad focus across neuroscience clinical studies, has the potential to reach many individuals who are affected by brain disorders."

The Medical Center's site -- dubbed UR NEXT -- has made significant contributions to the success and vitality of the network. URMC is the dominant provider of comprehensive neurological care in upstate New York with growing referral networks that have a regional, national, and international reach. This breadth of geographic reach and specialization of services has resulted in the Medical Center being one of the network's leading performers in terms of clinical trial recruitment and performance.

The Medical Center is also home to the Experimental Therapeutics in Neurological Disease post-doctoral training program now entering its 28th year of continuous funding from the National Institutes of Health, and the Center for Health + Technology (CHeT), a unique academic-research organization with decades of experience in development, management, and operation of multi-site clinical trials.

"The complexity of neurological diseases and the ever evolving nature of scientific innovation in this field mean that we must look always to the future and build the teams that turn new discoveries into new ways to diagnose, treat, and prevent these diseases," said Jonathan Mink, M.D., Ph.D., co-investigator on the grant who is leading Rochester's training of its investigators. "The UR NEXT grant will help us train the next generation of experts in leading and conducting multi-center clinical trials,"

In addition to URMC's role as a NeuroNEXT site, the Medical Center has two additional key roles supporting the national network. The URMC Clinical Materials Services Unit -- part of CHeT -- provides logistical support and drug supply distribution services for NeuroNEXT clinical trials and UR Labs provides central laboratory services for the network.

While We Sleep, Our Mind Goes on an Amazing Journey

Tuesday, July 17, 2018

A study by Maiken Nedergaard, a professor of neurosurgery, suggests that while we're awake, our neurons are packed tightly together, but when we're asleep, some brain cells deflate by 60 percent, widening the spaces between them. These intercellular spaces are dumping grounds for the cells' metabolic waste—notably a substance called beta-amyloid, which disrupts communication between neurons and is closely linked to Alzheimer's.

AHA Grants Will Accelerate Search for New Stroke Therapies

Wednesday, June 27, 2018

A series of awards from the American Heart Association (AHA) to a team of researchers at the University of Rochester Medical Center (URMC) will focus on the development of new treatments to thwart the damage in the brain caused by stroke.

One of the research projects brings together experts in stroke, cardiovascular biology, platelet biology, and peptide chemistry. Marc Halterman, M.D., Ph.D., with the URMC Center for Neurotherapeutics Discovery, Scott Cameron, M.D., Ph.D., and Craig Morrell, D.V.M., Ph.D., with the URMC Aab Cardiovascular Research Institute, and Bradley Nilsson, Ph.D., with the University of Rochester Department of Chemistry will focus on the role that platelets play in acute brain injury and inflammation during stroke.

Platelets serve an important role in protecting against blood loss and repairing injured blood vessels. However, during a stroke the inflammatory properties of platelets can interfere with the restoration of blood flow once the clot in the brain is removed, particularly in micro-vessels, which can lead to permanent damage of brain tissue.

The research team will build synthetic peptides that activate platelets to study the phenomenon -- which is called no-reflow -- in an effort to identify specific switches within platelets that can be turned off and limit the cells' inflammatory functions without blocking their ability to prevent bleeding.

Two AHA pre-doctoral fellowship awards Kathleen Gates and Jonathan Bartko in Halterman's lab will support research that examines the link between an immune system response triggered by stroke in the lungs that can exacerbate damage in the brain and investigate the cellular mechanisms that determine whether or not brain cells die following stroke.

A final AHA award to the Halterman lab will seek to identify new drug targets by focusing on specific proteins activated during stroke that are suspected to play an important role in determining the survival of neurons.

Collectively, the AHA Collaborative Sciences Award, Pre-Doctoral, and Innovation awards represent $1.09 million in funding.

Kevin Mazurek Receives CTSI Career Development Award

Friday, June 15, 2018

The University's Clinical and Translational Science Institute has selected the recipients of its Career Development Award, which provides two years of support to help early career scientists transition to independent careers as clinical and translational investigators. This year's awardees will study suicide prevention among Hispanic populations and how the brain controls voluntary movements.

Kevin A. Mazurek, research assistant professor of neuroscience, whose project is "Determining how Cortical Areas Communicate Information to Perform Voluntary Movements." Mazurek, whose primary mentor is John Foxe, professor of neuroscience, received his bachelor's degree in electrical engineering from Brown University in 2008 and his doctorate in electrical engineering from Johns Hopkins University in 2013. He studies the neural control of voluntary movements in order to develop rehabilitative solutions that can restore function to individuals with neurologic diseases by effectively bypassing impaired or damaged neural connections.

The Career Development program is supported by a KL2 award from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health. The UR CTSI Career Development Award Program releases its request for applications each September with applications due in November.

Neuroscience Grad Student Awarded NIH Diversity Fellowship

Tuesday, June 12, 2018

Monique S. Mendes, a neuroscience Ph.D. student, is the first University of Rochester Medical Center (URMC) graduate student to receive a prestigious diversity award from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders in Stroke (NINDS). Mendes works in the laboratory of Ania Majewska, Ph.D. and studies the role that the brain's immune cells play in development, learning, and diseases like Autism.

Monique S. Mendes, a neuroscience Ph.D. student, is the first University of Rochester Medical Center (URMC) graduate student to receive a prestigious diversity award from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders in Stroke (NINDS). Mendes works in the laboratory of Ania Majewska, Ph.D. and studies the role that the brain's immune cells play in development, learning, and diseases like Autism.

Mendes, originally from Kingston, Jamaica, received her undergraduate degree in Biology from the University of Florida. She came to URMC in search of a robust program that focused on glial biology and a collaborative environment. She chose the Del Monte Institute for Neuroscience to complete her thesis work due in part to Majewska's record of mentoring students and her lab's reputation for conducting leading research in brain development.

Mendes has been awarded a F99/K00 NIH Blueprint Diversity Specialized Predoctoral to Postdoctoral Advancement in Neuroscience (D-SPAN) fellowship from NINDS. The award was created to provide outstanding young neuroscientists from diverse backgrounds a pathway to develop independent research careers. Unlike traditional graduate student fellowships, this award provides research funding for 6 years, including dissertation research and mentored postdoctoral research career development.

Read the local Jamacian Observer newspaper article.

UR Medicine Recognized for Excellence in Stroke Care

Monday, June 11, 2018

The American Heart Association/American Stroke Association (AHA/ASA) has once again honored the UR Medicine Strong Memorial Hospital for having achieved the highest standard of care for stroke. This award identifies hospitals that provide care that can speed the recovery and reduce death and disability for stroke patients.

Strong Memorial Hospital has received the 2018 AHA/ASA Get With The Guidelines program's Stroke Gold Plus Quality Achievement Award. The hospital was also recognized for the Target: Stroke Honor Role Elite Plus designation, which identifies hospitals that have consistently and successfully reduced door-to-needle time -- the window of time between a stroke victim's arrival at the hospital, the diagnosis of an acute ischemic stroke, and the administration of the clot-busting drug tPA. If given intravenously in the first four and a half hours after the start of stroke symptoms, tPA has been shown to significantly reduce the effects of stroke and lessen the chance of permanent disability.

Ian Dickerson awarded University seed funding

Tuesday, May 29, 2018

University Research Awards, which provide "seed" grants for promising research, have been awarded to 15 projects for 2018-19. The projects range from an analysis of the roles of prisons in the Rochester region, to a new approach to genome editing, to new initiatives for advanced materials for powerful lasers.

The funding has been increased from $500,000 to $1 million. Half of the funding comes from the President's Fund, with the rest being matched by the various schools whose faculty members are recipients.

Ian Dickerson, associate professor of neuroscience, and Joseph Miano, professor, Aab Cardiovascular Research Institute received the funding for "Pre-clinical mouse model for atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (aHUS)".

URMC Researcher Featured in Academic Stories

Tuesday, May 29, 2018

Kevin Mazurek, PhD recently gave an interview for the online Academic Stories blog, entitled "Researchers Discover How to Inject Instructions into the Premotor Cortex".

"Thanks to our brain's complex network of connections, we are able to effortlessly move through and react to the world around us. But for people with strokes or traumatic brain injuries, these connections are disrupted making some basic functions challenging. Kevin Mazurek and his mentor Marc Schieber at the University of Rochester have made a discovery with the potential to help restore neural connections in patients. They have found a way to "inject" information directly into the premotor cortex of two rhesus monkeys, bypassing the visual centres."

Academic Stories, a division of Academic Media Group, aims to inspire more people to pursue academic careers by sharing groundbreaking research and the people and places that make it possible. Academic Stories brings their stories to a larger audience in an accessible way.

Syd Cash, MD, PhD Delivers Elizabeth Doty Lecture

Thursday, May 24, 2018

Sydney S. Cash, M.D., Ph.D. presented, "Multiscale Studies of Human Cortical Oscillations during Sleep and Cognition" for the Elizabeth Doty lecture. Sydney comes to us from Harvard University and Massachusetts General Hospital where his research is dedicated to trying to understand normal and abnormal brain activity using multi-modal and multi-scalar approaches.

Sydney S. Cash, M.D., Ph.D. presented, "Multiscale Studies of Human Cortical Oscillations during Sleep and Cognition" for the Elizabeth Doty lecture. Sydney comes to us from Harvard University and Massachusetts General Hospital where his research is dedicated to trying to understand normal and abnormal brain activity using multi-modal and multi-scalar approaches.

The Department of Neuroscience hosts the Elizabeth Doty Lectureship each year to honor Robert W. Doty, PhD, an esteemed member of the department, who created this neuroscience lectureship in memory of his wife and the 58 years they shared in marriage. A particular passion of Dr. Doty's was his quest to understand the meaning of consciousness and its underlying neural basis. Each year the committee invites an accomplished neuroscientist to present a lecture that will address in some way how the workings of the mind derive from neuronal activity. The intent of the Lecture is to appeal to a wide and diverse audience to include all interested in the neural sciences -- faculty, alumni, students, and other scholars.

The Department of Neuroscience hosts the Elizabeth Doty Lectureship each year to honor Robert W. Doty, PhD, an esteemed member of the department, who created this neuroscience lectureship in memory of his wife and the 58 years they shared in marriage. A particular passion of Dr. Doty's was his quest to understand the meaning of consciousness and its underlying neural basis. Each year the committee invites an accomplished neuroscientist to present a lecture that will address in some way how the workings of the mind derive from neuronal activity. The intent of the Lecture is to appeal to a wide and diverse audience to include all interested in the neural sciences -- faculty, alumni, students, and other scholars.

Brain Science Suggests This Is the Best Position to Sleep In

Thursday, May 17, 2018

Sleep is critical for rest and rejuvenation. A human being will actually die of sleep deprivation before starvation--it takes about two weeks to starve, but only 10 days to die if you go without sleep.

The CDC has also classified insufficient sleep as a public health concern. Those who don't get enough sleep are more likely to suffer from chronic diseases that include hypertension, diabetes, depression, obesity, and cancer.

It's thus vital to get enough shuteye, but it turns out your sleep position also has a significant impact on the quality of rest you get.

In addition to regulating one's appetite, mood, and libido, neuroscientists assert that sleep reenergizes the body's cells, aids in memory and new learning, and clears waste from the brain.

That last one is particularly important. Similar to biological functions in which your body clears waste, your brain needs to get rid of unwanted material. The more clearly it functions, the more clearly you do.

Now, a neuroscience study suggests that of all sleep positions, one is most helpful when it comes to efficiently cleaning out waste from the brain: sleeping on your side.

The study, published in the Journal of Neuroscience, used dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI to image the brain's "glymphatic pathway." This is the system by which cerebrospinal fluid filters through the brain and swaps with interstitial fluid (the fluid around all other cells in the body).

The exchange of the two fluids is what allows the brain to eliminate accumulated waste products, such as amyloid beta and tau proteins. What are such waste chemicals associated with? Among other conditions, Alzheimer's and Parkinson's.

"It is interesting that the lateral [side] sleep position is already the most popular in humans and most animals--even in the wild," said University of Rochester's Maiken Nedergaard. "It appears that we have adapted the lateral sleep position to most efficiently clear our brain of the metabolic waste products that build up while we are awake."

Rochester Research Cited in Psychology Today Article

Monday, May 14, 2018

Work in the Schieber lab by Marc Schieber and Kevin Mazurek was included in "The Sensory Revolution" in Psychology Today.

Our senses are under constant threat from the stimuli, routines, and ailments of the modern world. Fortunately, neuroscience is inspiring remedies that not only restore sensory input but radically alter it.

Sometimes sensation makes its way to the brain but doesn't alter behavior because the brain's wiring fails, as in stroke or localized brain damage. Neuroscientists Marc Schieber and Kevin Mazurek, both at the University of Rochester, have demonstrated a method that might bypass these downed lines. They've trained two monkeys to perform four instructed actions, such as turning a knob or pressing a button. But that instruction takes the form of an electrical signal sent to electrodes in the monkeys' premotor cortex, an area between the sensory cortices and the motor cortex, which controls muscle movement. Even without any sensory instruction, the monkeys were nearly 100 percent accurate at interpreting the signal and performing the correct action.

Words from Wallis Hall: The University's Neuroscience Network

Friday, May 11, 2018

University president Richard Feldman in the latest Words from Wallis Hall has recognized the efforts of the Del Monte Institute for Neurosciences in making Rochester a leader in the field of neuroscience.

"The Del Monte Institute for Neuroscience has been instrumental in bringing together neuroscience and related research at the Medical Center and the River Campus. That interdisciplinary work and our history in the field have helped make Rochester an important player in neuroscience, and have helped sharpen our focus and further critical research into Alzheimer's and intellectual and developmental disabilities such as autism and dyslexia," says Feldman.

Schieber lab publishes paper in Journal of Neuroscience

Wednesday, May 2, 2018

Kevin Mazurek, Adam Rouse, and Marc Schieber published a manuscript in the Journal of Neuroscience on May 2, 2018 entitled "Mirror Neuron Populations Represent Sequences of Behavioral Epochs During Both Execution and Observation"

Liz Romanski Awarded R21 from NIDCD

Tuesday, May 1, 2018

The Romanski lab has been awarded an R21 grant from the NIDCD entitled, "Audiovisual Processing in Temporal-Prefrontal Circuits."

Congratulation Liz!

Neuroscience Lab Holds ‘Brain Day’ at Local School

Monday, April 30, 2018

Last Friday, staff from the Del Monte Neuroscience Institute's Cognitive Neurophysiology Laboratory (CNL) spent the afternoon at the Hope Hall School explaining the mysteries of the human brain and exposing students to careers in STEM fields.

The Hope Hall School, located in Gates, serves students with special learning needs in grades 2 through 12 from school districts across the greater Rochester area. Similar events at other schools in the area are being planned by the CNL staff.

Krishnan Padmanabhan Recognized as a Polak Young Investigator

Tuesday, April 24, 2018

Krishnan Padmanabhan, PhD was recently awarded one of the 2018 Polak Young Investigator Awards by the Association for Chemoreception Sciences (AChemS).

The purpose of this award is to encourage and recognize innovative research at the annual conference by young investigators. The Incoming Program Chair, with help from the Program Committee will select 5-6 young investigators based upon the scientific merit of their abstract submission. Each selected investigator will deliver an oral slide presentation during the AChemS meeting (or satellite conference). The abstract will be organized within the program-at-large by scientific topic and presenters will be recognized as Polak Young Investigators during the introduction of their presentations by the session chair or the abstracts may be presented in one awards session.

Congratulations Dr. Padmanabhan!!

Dr. Mazurek receives award at national convention

Saturday, April 21, 2018

Kevin Mazurek received a Future Clinical Researcher Scholarship Award from the American Academy of Neurology (AAN) to present a platform presentation at the AAN Annual Meeting held in Los Angeles, California (April 21 - 27).

National Initiative Focuses on New Treatments for Lewy Body Dementia

Wednesday, April 18, 2018

The University of Rochester Medical Center (URMC) has been selected to participate in a national network created to develop new ways to diagnose and treat Lewy Body Dementia (LBD). The new initiative, which is being organized by the Lewy Body Dementia Association, will seek to raise awareness and advance research for this complex disorder.

"Lewy Body Dementia is a challenging, multifaceted disease and research to find new diagnostic tools and treatments is still in its infancy," said URMC neurologist Irene Richard, M.D., who will serve as director of the URMC Lewy Body Dementia Association Research Center of Excellence. "This new network of will create an infrastructure of clinician researchers who understand the disease, are able to identify patients to participate in research, and have experience participating in multi-site clinical trials."

LBD is a progressive brain disorder marked by abnormal protein deposits -- called Lewy Bodies -- in areas of the brain important for behavior, cognition, and motor control. This complex disease gives rise to a range of symptoms, including cognitive impairment, sleep disturbances, hallucinations, difficulty with blood pressure regulation, and problems with movement and balance. Individuals with the disease will often experience marked fluctuations in their levels of alertness and clarity of thought.

Mobile Apps Could Hold Key to Parkinson’s Research, Care

Monday, March 26, 2018

By Mark Michaud

A new study out today in the journal JAMA Neurology shows that smartphone software and technology can accurately track the severity of the symptoms of Parkinson's disease. The findings could provide researchers and clinicians with a new tool to both develop new drugs and better treat this challenging disease.

"This study demonstrates that we can create both an objective measure of the progression of Parkinson's and one that provides a richer picture of the daily lived experience of the disease," said University of Rochester Medical Center (URMC) neurologist Ray Dorsey, M.D., a co-author of the study.

One of the difficulties in managing Parkinson's is that symptoms of the disease can fluctuate widely on a daily basis. This makes the process of tracking the progression of the disease and adjusting treatment a challenge for physicians who may only get a snapshot of a patient's condition once every several months when they visit the clinic. This variation also limits the insight that researchers can gather on the effectiveness of experimental treatments.

The new study, which was led by Suchi Saria, Ph.D., an assistant professor of Computer Science at Johns Hopkins University, harnesses the capabilities of technology that already resides in most of our pockets all day, every day.

Researchers recruited 129 individuals who remotely completed a series of tasks on a smartphone application. The Android app called HopkinsPD, which was originally developed by Max Little, Ph.D., an associate professor of Mathematics at Aston University in the U.K., consists of a series of tasks which measure voice fluctuations, the speed of finger tapping, walking speed, and balance.

The Android app is a predecessor to the mPower iPhone app which was developed by Little, Dorsey, and Sage Bionetworks and has been download more than 15,000 times from Apple's App Store since its introduction in 2015.

As a part of the study, the researchers also conducted in-person visits with 50 individuals with Parkinson's disease and controls in the clinic at URMC. Participants were asked to complete the tasks on the app and were also seen by a neurologist and scored using a standard clinical evaluation tool for the disease. This aspect of the study was overseen by URMC's Center for Health + Technology.

New Career Development Awardees to Study Suicide Prevention and Neural Processing

Monday, March 12, 2018

Kevin Mazurek, Ph.D., postdoctoral fellow in the Department of Neurology at URMC, will investigate how areas of the brain communicate information about how and why movements are performed and how neurologic diseases such as epilepsy affect this communication.

Electrophysiological techniques allow for investigating which cortical areas communicate information related to the performance of voluntary movements. For his KL2 project, Dr. Mazurek will analyze changes in neural communication as participants perform the same hand and finger movements when instructed with different sensory cues (e.g. visual, auditory). He will compare healthy individuals and individuals with intractable epilepsy to identify changes in neural communication pathways. Identifying the exact nature in which epileptic activity affects cortical communication could lead to a biomarker for the appropriate connections to target for rehabilitative treatment.

Professor Studies Complex Brain Networks Involved in Vision

Monday, March 12, 2018

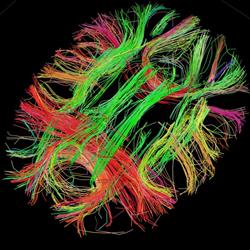

Our brains are made up of an intricate network of neurons. Understanding the complex neuronal circuits—the connections of these neurons—is important in understanding how our brains process visual information.

Farran Briggs, a new associate professor of neuroscience and of brain and cognitive sciences at the University of Rochester, studies neuronal circuits in the brain's vision system and how attention affects the brain's ability to process visual information.

Previously a professor at the Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, Briggs became interested in neuroscience in high school. "I took a class and just became really fascinated by the brain and how it works," she says. Today, her research on the fundamental levels of vision may provide new insight on impairments associated with attention deficit disorders.

Biological Sex Tweaks Nervous System Networks, Plays Role in Shaping Behavior

Thursday, March 8, 2018

By Mark Michaud

New research published today in the journal Current Biology demonstrates how biological sex can modify communication between nerve cells and generate different responses in males and females to the same stimulus. The findings could new shed light on the genetic underpinnings of sex differences in neural development, behavior, and susceptibility to diseases.

"While the nervous systems of males and females are virtually identical, we know that there is a sex bias in how many neurological diseases manifest themselves, that biological sex can influence behavior in animals, and that some of these differences are likely to be biologically driven," said Douglas Portman, Ph.D., an associate professor in the Departments of Biomedical Genetics, Neuroscience, and the Center for Neurotherapeutics Discovery at the University of Rochester Medical Center (URMC) and lead author of the study. "This study demonstrates a connection between biological sex and the control and function of neural circuits and that these different sex-dependent configurations can modify behavior."

The findings were made in experiments involving the nematode C. elegans, a microscopic roundworm that has long been used by researchers to understand fundamental mechanisms in biology. Many of the discoveries made using these worms apply throughout the animal kingdom and this research has led to a broader understanding of human biology. In fact, three Nobel Prizes in medicine and chemistry have been awarded for discoveries involving C. elegans.

The study focuses on the different behaviors of male and female worms. There are two sexes of C. elegans, males and hermaphrodites. Although the hermaphrodites are able to self-fertilize, they are also mating partners for males, and are considered to be modified females.

The behavior of C. elegans is driven by sensory cues, primarily smell and taste, which are used by the worms to navigate their environment and communicate with each other. Female worms secrete a pheromone that is known to attract males who are drawn by this signal in search of a mate. Other females, however, are repelled by the same pheromone. It is not entirely understood why, but scientists speculate that that the pheromone signals to females to avoid areas where there may be too much competition.

URMC Investigating New Parkinson's Drug

Wednesday, February 28, 2018

The University of Rochester Medical Center Clinical Trials Coordination Center (CTCC) has been tapped to help lead a clinical trial for a potential new treatment for Parkinson's disease. The study will evaluate nilotinib, a drug currently used to treat leukemia that has shown promise in early studies in people with Parkinson's disease.

Cynthia Casaceli, M.B.A., the director of the CTCC, will oversee the operations of the study, which will be conducted through the Parkinson Study Group at 25 sites across the U.S. URMC is not a recruiting site for the study. The clinical trial is being led by Tanya Simuni, M.D., with Northwestern University and supported by the Michael J. Fox Foundation.

Nilotinib is a FDA-approved treatment for chronic myelogenous leukemia. The drug inhibits the activity of c-Abl, a protein that can accumulate in toxic levels in the brain and has been linked to cellular pathways associated with Parkinson's disease.

Brain Signal Indicates When You Understand What You’ve Been Told

Friday, February 23, 2018

During everyday interactions, people routinely speak at rates of 120 to 200 words per minute. For a listener to understand speech at these rates – and not lose track of the conversation – the brain must comprehend the meaning of each of these words very rapidly.

“That we can do this so easily is an amazing feat of the human brain – especially given that the meaning of words can vary greatly depending on the context,” says Edmund Lalor, associate professor of biomedical engineering and neuroscience at the University of Rochester and Trinity College Dublin. “For example, ‘I saw a bat flying overhead last night’ versus ‘the baseball player hit a home run with his favorite bat.’”

Now, researchers in Lalor’s lab have identified a brain signal that indicates whether a person is indeed comprehending what others are saying – and have shown they can track the signal using relatively inexpensive EEG (electroencephalography) readings taken on a person’s scalp.

Drinking Alcohol Tied To Long Life In New Study

Thursday, February 22, 2018

Drinking could help you live longer—that's the good news for happy-hour enthusiasts from a study presented last week at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science. According to the study, people who live to 90 or older often drink moderately.

Neurologist Claudia Kawas and her team at the University of California, Irvine, have been studying the habits of people who live until their 90s since 2003. There’s a paltry amount of research on the oldest-old group, defined as 85 and older by the Social Security Administration, and Kawas wanted to delve into the lifestyle habits of those who live past 90. She began asking about dietary habits, medical history and daily activities via survey, wondering if such data could help identify trends among these who lived longest. Ultimately she gathered information on the habits of 1,700 people between the ages of 90-99.

In general, research on alcohol has shown mixed results. A recent study published in Scientific Reports showed that drinking might help clear toxins from the brain. The study was conducted on mice, who were given the human equivalent of two and a half alcoholic beverages.

Dr. Maiken Nedergaard of the University of Rochester Medical Center told Newsweek at the time that alcohol did have real health benefits. “Except for a few types of cancer, including unfortunately breast cancer, alcohol is good for almost everything,” Nedergaard said.

Training brains—young and old, sick and healthy—with virtual reality

Tuesday, February 13, 2018

An accidental discovery by Rochester researchers in 2003 touched off a wave of research into the area of neuroplasticity in adults, or how the brain's neural connections change throughout a person's lifespan.

Fifteen years ago, Shawn Green was a graduate student of Daphne Bavelier, then an associate professor of brain and cognitive sciences at the University. As the two created visual tests together, Green demonstrated exceptional proficiency at taking these tests himself. The two researchers hypothesized that it might be due to his extensive experience playing first-person, action-based video games. From there, Green and Bavelier demonstrated that, indeed, action-based video games enhance the brain's ability to process visual information.

In years since, video gaming technology has gotten more sophisticated, regularly incorporating or featuring virtual reality (VR). The Oculus Rift headset, for example, connects directly to your PC to create an immersive VR gaming experience.

If we know that action-based video games enhance visual attention, might VR games do the same (and perhaps to a greater degree) because of the increased level of immersion?

That's the question a current group of Rochester researchers—Duje Tadin, associate professor of brain and cognitive sciences; Jeffrey Bazarian, professor of emergency medicine; and Feng (Vankee) Lin, assistant professor in the School of Nursing—hope to answer.

In Wine, There’s Health: Low Levels of Alcohol Good for the Brain

Friday, February 2, 2018

By Mark Michaud

While a couple of glasses of wine can help clear the mind after a busy day, new research shows that it may actually help clean the mind as well. The new study, which appears in the journal Scientific Reports, shows that low levels of alcohol consumption tamp down inflammation and helps the brain clear away toxins, including those associated with Alzheimer's disease.

"Prolonged intake of excessive amounts of ethanol is known to have adverse effects on the central nervous system," said Maiken Nedergaard, M.D., D.M.Sc., co-director of the Center for Translational Neuromedicine at the University of Rochester Medical Center (URMC) and lead author of the study. "However, in this study we have shown for the first time that low doses of alcohol are potentially beneficial to brain health, namely it improves the brain's ability to remove waste."

The finding adds to a growing body of research that point to the health benefits of low doses of alcohol. While excessive consumption of alcohol is a well-documented health hazard, many studies have linked lower levels of drinking with a reduced risk of cardiovascular diseases as well as a number of cancers.

Lungs Mays Hold Key to Thwarting Brain Damage after a Stroke

Wednesday, January 31, 2018

By Mark Michaud

The harm caused by a stroke can be exacerbated when immune cells rush to the brain an inadvertently make the situation worse. Researchers at the University of Rochester Medical Center (URMC) are studying new ways to head off this second wave of brain damage by using the lungs to moderate the immune system's response.

"It has become increasingly clear that lungs serve as an important regulator of the body's immune system and could serve as a target for therapies that can mitigate the secondary damage that occurs in stroke," said URMC neurologist Marc Halterman, M.D., Ph.D. "We are exploring a number of drugs that could help suppress the immune response during these non-infection events and provide protection to the brain and other organs."

Halterman's lab, which is part of the Center for NeuroTherapeutics Discovery, has been investigating domino effect that occurs after cardiac arrest. When blood circulation is interrupted, the integrity of our intestines becomes compromised, releasing bacteria that reside in the gut into the blood stream. This prompts a massive immune response which can cause systemic inflammation, making a bad situation worse.

While looking at mouse models of stroke, his lab observed that a similar phenomenon occurs. During a stroke blood vessels in the brain leak and the proteins that comprise the wreckage of damaged neurons and glia cells in the brain make their way into blood stream. The immune system, which is not used to seeing these proteins in circulation, responds to these damage-associated molecular patterns and ramps up to respond. Mobilized immune cells make their way into the brain and, finding no infection, nevertheless trigger inflammation and attack healthy tissue, compounding the damage.

The culprit in this system-wide immune response is neutrophils, a white cell in the blood system that serves as the shock troops of the body's immune system. Because our entire blood supply constantly circulates through the lungs, the organ serves as an important way station for neutrophils. It is here that the cells are often primed and instructed to go search for new infections. The activated neutrophils can also cause inflammation in the lungs, which Halterman suspects may be mistakenly identified as post-stroke pneumonia. The damage caused by activated neutrophils can also spread to other organs including the kidneys, and liver.

Remembering a Pioneer of Environmental Health Science

Wednesday, January 31, 2018

By Pete Myers, Richard Stahlhut, Joan Cranmer, Steven Gilbert, Shanna Swan

Colleagues honor Bernard "Bernie" Weiss (1925-2018)—a remarkable scientist, thinker, visionary and writer