Epilepsy and Seizures

What is epilepsy?

Epilepsy is a brain condition that causes a person to have recurring seizures that aren't caused by a short-term (temporary) health condition. It's one of the most common disorders of the nervous system. It affects people of all ages and backgrounds.

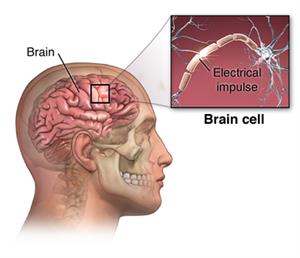

The brain consists of nerve cells that communicate with each other through electrical activity. A seizure happens when 1 or more parts of the brain has a burst of abnormal electrical signals that interrupt normal brain signals. Anything that interrupts the normal connections between nerve cells in the brain can cause a seizure. This includes a high fever, high or low blood sugar, alcohol or illegal drug withdrawal, or a brain concussion. But when a person has recurrent seizures that aren't from a temporary health problem, this is diagnosed as epilepsy.

There are different types of seizures. The type of seizure depends on which part and how much of the brain is affected and what happens during the seizure. The 2 main categories of epileptic seizures are focal (partial) seizure and generalized seizure. Focal seizures can spread to become generalized seizures.

Focal (partial) seizures

Focal (or partial) seizures take place when abnormal electrical brain function happens in 1 or more areas of 1 side of the brain. Before a focal seizure, you may have an aura or signs that a seizure is about to happen. Common auras involve feelings, such as deja vu, impending doom, fear, or euphoria. Or you may have visual changes, hearing abnormalities, or changes in your sense of smell. The 2 types of focal seizures are:

-

Impaired awareness (previously called complex partial seizure)

-

Retained awareness (previously called simple partial seizure)

The symptoms depend on which part of the brain is affected. If the abnormal electrical brain function is in the part of the brain involved with vision (occipital lobe), your sight may be altered. More often, muscles are affected. The seizure activity is limited to an isolated muscle group. For example, it may only include the fingers, or larger muscles in the arms and legs. You may also have sweating, nausea, or become pale.

You may just stop being aware of what's going on around you. You may look awake, but have a variety of abnormal behaviors. These may range from gagging, lip smacking, running, screaming, crying, or laughing. You may be tired or sleepy after the seizure. This is called the postictal period.

Generalized seizure

A generalized seizure happens in both sides of the brain. You will lose consciousness and be tired after the seizure (postictal state). Types of generalized seizures include:

Absence seizures previously called petit mal seizure. This seizure causes a brief changed state of consciousness and staring. You will likely maintain your posture. Your mouth or face may twitch or your eyes may blink rapidly. The seizure often lasts no longer than 30 seconds. When the seizure is over, you may not recall what just occurred. You may go on with your activities as though nothing happened. These seizures may occur a few times a day or many times.

Atonic seizure or drop attack. With an atonic seizure, you have a sudden loss of muscle tone and may fall from a standing position or suddenly drop your head. During the seizure, you will be limp and unresponsive.

Tonic clonic or grand mal seizure. The most well-known form of seizure. Your body, arms, and legs will flex (contract), extend (straighten out), and tremor (shake). This is followed by contraction and relaxation of the muscles (clonic period) and the postictal period. During the postictal period, you may be sleepy. You may have problems with vision or speech, and may have a bad headache, fatigue, or body aches. Not all of these phases occur in everyone with this type of seizure.

Myoclonic seizures. This type of seizure causes quick movements or sudden jerking of a group of muscles. These seizures tend to occur in clusters. This means that they may occur several times a day.

What causes a seizure?

A seizure can be caused by many things. Anything that irritates the brain or causes nerve cells to have abnormal electrical activity can cause a seizure. These can include:

-

An imbalance of nerve-signaling brain chemicals (neurotransmitters)

-

Brain tumor

-

Stroke

-

Brain damage from birth, illness, past brain surgery, or injury

-

Infection (meningitis, encephalitis)

-

Hereditary epilepsy, when your genes cause you to have seizures

-

Health conditions that alter the normal electrical activity of the brain, such as:

-

Illegal drug use or some medicines

-

Withdrawal of alcohol or medicines

-

Abnormal glucose levels or levels of electrolytes in your blood (like sodium)

-

Epilepsy may be caused by a combination of these. In most cases, the cause of epilepsy can’t be found.

What are the symptoms of a seizure?

Your symptoms depend on the type of seizure. General symptoms or warning signs of a seizure can include:

-

Staring

-

Jerking movements of the arms and legs

-

Stiffening of the body

-

Loss of consciousness

-

Breathing problems or stopping breathing

-

Loss of bowel or bladder control

-

Falling suddenly for no apparent reason, especially when linked to loss of consciousness

-

Not responding to noise or words for brief periods

-

Appearing confused or in a haze

-

Nodding your head rhythmically, when linked to loss of awareness or loss of consciousness

-

Periods of rapid eye blinking and staring

During the seizure, your lips may become tinted blue and your breathing may not be normal. After the seizure, you may be sleepy or confused.

The symptoms of a seizure may be like those of other health conditions. Make sure to talk with your healthcare provider for a diagnosis.

How are seizures diagnosed?

Your healthcare provider will ask about your symptoms and your health history. You’ll be asked about other factors that may have caused your seizure, such as:

-

Drug or alcohol use

-

A history of head injury

-

High fever or infection

-

Genetic abnormality

You may also have:

-

A nervous system exam

-

Blood tests to check for problems in blood sugar and other factors

-

Imaging tests of the brain, such as an MRI or CT scan

-

Electroencephalogram (EEG) to test your brain's electrical activity

-

Lumbar puncture (spinal tap) to measure the pressure in the brain and spinal canal and test the cerebrospinal fluid for infection or other problems

How are seizures treated?

The goal of treatment is to control, stop, or reduce how often seizures happen. Treatment is usually done with medicine. There are many types of medicines used to treat epilepsy. Your healthcare provider will need to identify the type of seizure you are having. Medicines are chosen based on the type of seizure, your age, side effects, cost, and ease of use. Medicines used at home are often taken by mouth such as capsules, tablets, sprinkles, or syrup. Some medicines can be given into the rectum. If you are in the hospital with seizures, medicine may be given by injection or by IV (intravenous) into a vein.

It's important to take your medicine on time and as prescribed by your healthcare provider. People’s bodies react to medicine differently so your schedule and dosage may need to be adjusted for the best seizure control. All medicines can have side effects. Talk with your healthcare provider about possible side effects. While you are taking medicine, you may need tests to see how well the medicine is working. You may have:

-

Blood tests. You may need blood tests often to check the level of medicine in your body. Based on this level, your healthcare provider may change the dose of your medicine. You may also have blood tests to check the effects of the medicine on your other organs.

-

Pee tests. Your pee may be tested to see how your body is reacting to the medicine.

-

EEG. This test records the brain's electrical activity. This is done by attaching electrodes to your scalp. This test is done to see how medicine is helping the electrical problems in your brain.

-

EEG monitoring. This is when the EEG is hooked up for a prolonged time. This can be done with you at home or in the hospital. Sometimes video is recorded at the same time to see if the EEG explains the seizure.

Other treatments

If medicine doesn’t work well enough for you, your healthcare provider may advise other types of treatment. Second opinions from epilepsy specialists can help you feel better about the treatment decisions you might face.

Vagus nerve stimulator (VNS)

This treatment sends small pulses of energy to the brain from one of the vagus nerves. This is a pair of large nerves in the neck. If you have partial seizures that aren't controlled well with medicine, VNS may be an option.

VNS is done by surgically placing a small battery into the chest wall. Small wires are then attached to the battery and placed under the skin and around one of the vagus nerves. The battery is then programmed to send energy impulses every few minutes to the brain. When you feel a seizure coming on, you may activate the impulses by holding a small magnet over the battery. In many cases, this will help to stop the seizure. VNS can have side effects, such as hoarse voice, pain in the throat, or change in voice.

Surgery

Surgery may be done to remove the part of the brain where the seizures are occurring. Or the surgery helps to stop the spread of the bad electrical currents through the brain. Surgery may be an option if your seizures are hard to control and always start in a part of the brain that doesn’t affect speech, memory, or vision.

Surgery for epilepsy seizures is very complex. It's done by a specialized surgical team. You may be awake during the surgery. The brain itself doesn't feel pain. If you are awake and able to follow commands, the surgeons are better able to check areas of your brain during the procedure. A special epilepsy team makes a report (comprehensive, complex diagnostic workup) to see if you are a good candidate for surgery. Surgery is not an option for everyone with seizures.

Living with epilepsy

If you have epilepsy, you can manage your health. Make sure to:

-

Take your medicine exactly as advised

-

Keep a seizure diary and bring it with you to your appointments. Include the time, date, length, and type of seizure that occurred and any trigger linked to it.

-

Contact your provider if the seizures change in how they appear, how often they happen, and how long they last. They may need to adjust your medicine.

-

Contact your provider if you have medicine side effects. Never stop taking medicines on your own. This can lead to serious withdrawal problems.

-

Get enough sleep, as lack of sleep can trigger a seizure

-

Stay away from anything that may trigger a seizure

-

Have tests as often as needed

-

If your seizures make you disabled, learn about the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) so you are aware of your legal protections.

-

See your healthcare provider regularly

When should I call my healthcare provider?

Call your healthcare provider if:

-

Your symptoms get worse or don't get better

-

You have side effects from medicine

-

You have new symptoms

Key points about epilepsy and seizures

-

A seizure occurs when 1 or more parts of the brain has a burst of abnormal electrical signals that interrupt normal signals.

-

There are many types of seizures. Each can cause different kinds of symptoms. These range from slight body movements to loss of consciousness and convulsions.

-

Epilepsy is when you have 2 or more seizures not due to a temporary health problem.

-

Epilepsy is treated with medicine. In some cases, it may be treated with vagus nerve stimulator or surgery.

-

It’s important to stay away from anything that triggers seizures. This includes lack of sleep.

Next steps

Tips to help you get the most from a visit to your healthcare provider:

-

Know the reason for your visit and what you want to happen.

-

Before your visit, write down questions you want answered.

-

Bring someone with you to help you ask questions and remember what your provider tells you.

-

At the visit, write down the name of a new diagnosis, and any new medicines, treatments, or tests. Also write down any new instructions your provider gives you.

-

Know why a new medicine or treatment is prescribed, and how it will help you. Also know what the side effects are.

-

Ask if your condition can be treated in other ways.

-

Know why a test or procedure is recommended and what the results could mean.

-

Know what to expect if you do not take the medicine or have the test or procedure.

-

If you have a follow-up appointment, write down the date, time, and purpose for that visit.

-

Know how you can contact your provider if you have questions, especially after office hours and on weekends and holidays.

Medical Reviewers:

- Anne Fetterman RN BSN

- Callie Tayrien RN MSN

- Raymond Kent Turley BSN MSN RN