In my women’s group, much of our conversation is about weight gain. All my doctors tell me that in order to lose weight, I need to change my diet and get rid of carbs. Isn’t exercise part it?

Your Menopause Question: In my women’s group, most of us are going through menopause, and much of our conversation is about weight gain. All my doctors tell me that in order to lose weight, I need to change my diet and get rid of carbohydrates. I walk my dog each day. Isn’t exercise part of the discussion?

Our Response: Your doctor is correct but should have explained it better. The conversation for women in menopause should involve diet and exercise, but it also should take into account one’s age and hormone management. The good news is that applying these concepts will extend one’s lifetime health (Caprara, 2018).

Let’s discuss exercise first. Moderate exercise is critical for a healthy lifestyle. Having said that, exercise moves fat to muscle, and muscle has weight. So while exercise helps the mind and tones the body, exercise alone will not result in weight loss unless that effort is combined with a focus on diet. If one changes her diet to reduce weight, exercise will help maintain that new weight.

Which brings us to diet. The various dietary plans sound easy but may be more difficult to adhere to. How many times have you heard a friend say, “I am on the South Beach Diet,” or “I follow the Mediterranean diet”? Yet, when asked what they had for dinner the night before, pasta, one or two glasses of wine, and dessert suggest an incomplete commitment to dietary change.

There are times when introducing a new dietary plan runs up against reality. If you are feeding kids, then pizza, macaroni and cheese, or goulash may dominate the menu, if for no other reason than to provide a quick and easy meal. Or, if your partner insists on meat and potatoes and a beer, the move to a more healthy diet plan becomes a challenge.

Still, all dietary programs appear to focus on increasing protein intake and decreasing consumption of carbohydrates. What does that mean? Recall, 45% to 65% of our energy comes from carbohydrates, so normally this would amount to 225 to 325 gm per day (Holesh, 2021).

The basis of the Mediterranean diet, popularized following the Second World War, includes plant-based food like fruits, vegetables, whole grains, legumes (green beans), and nuts. Olive oil and canola oil substitute for butter. Herbs and spices substitute for salt. Fish, like mackerel, herring, salmon, and tuna, offer omega-3 fatty acids. Approximately 60% to 65% of the calories of the Mediterranean diet are comprised of complex carbohydrates with less than 10% simple sugars, 10% proteins, and 25% to 35% fats.

The basis of the South Beach Diet, published first by Arthur Agatston in 2003, balances complex carbohydrates, lean protein, and healthy fats, and therefore, is a modified low-carbohydrate diet. This plan recommends limiting carbohydrates to 28% of daily calories or 140 gm per day. The keto version of the South Beach Diet limits carbohydrates to 40 gm per day in phase one and 50 gm per day in phase two, the intent being to encourage the body to burn fat for fuel.

Recall, strict, low-carb diets may restrict carbohydrate intake to as little as 20 gm per day.

All of these “plans” seem to imply that the solution to weight gain and even protection from cardiovascular and diabetic risk is simply to eliminate carbs. Well, it is not as simple as that. According to the Cleveland Clinic (2018), the four most common myths about carbohydrates are: 1. Carbs make you gain weight; 2. Only white food contains carbs; 3. All white foods should be avoided; and 4. Fruit is bad because it is high in carbs.

So, what do we really know about carbohydrates? Metabolism begins in the mouth as salivary amylase starts to break down the carbohydrates. Simple sugars, called monosaccharides, include glucose, galactose, and fructose, which are rapidly absorbed into the bloodstream. Our pancreas releases insulin, which causes cells to take in the monosaccharides for energy or storage. As the insulin transports glucose out of the blood into cells, it creates low blood glucose levels which, in animal and human studies, result in increased hunger and increased eating (Geiselman, 1982, and Yau, 2017).

Complex carbohydrates, made up of three or more sugars, include oligosaccharides and polysaccharides in apples, broccoli, lentils, spinach, and brown rice. Absorption is slower and avoids the quick peaks of blood glucose that monosaccharides produce (Holesh, 2021).

Starches, characterized as complex carbohydrates produced exclusively by plants, are composed of a large number of glucose molecules. Starches are produced by plants during the day but at night utilize the glucose for fuel or storage. Starches consist of two forms, amylose, which makes up 23% to 30% of all starches that are resistant to digestion, and amylopectin, which accounts for 70% to 80% of all starches that are more digestible.

Dietary digestion of starch begins in the oral cavity where amylase enzyme breaks starch to maltose. Maltose, in turn, releases the glucose molecules in the intestine for absorption into the bloodstream. Starch, therefore, is one of the major sources of carbohydrates in our diet and includes potatoes, chick peas, and pasta (Zeeman, 2010).

Fiber is a broad category of plant composition made up of two distinct types that differ in chemical makeup, water-holding capacity, bile acid binding, weight control (by slowing the rate of digestion), and insulin sensitivity (Burton-Freeman, 2017). Since humans lack the enzymes to digest them, insoluble fibers, including wheat bran and cellulose (roots and leafy vegetables), are known to draw in water to increase bulk and decrease transit time to improve defecation.

Soluble fibers such as fleshy fruits, oats, broccoli, and dried beans are linked to reduced cholesterol and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) and blunt the postprandial blood glucose increase that occurs after meals.

So where does this information help?

The standard measure of carbohydrate intake, called the glycemic index, ranks carbohydrates from 1 to 100 based on the immediate rise in blood glucose upon consumption (Lazarim, 2009). Low glycemic foods produce a slower rise in blood glucose levels as is observed after eating steel-cut oatmeal, oat bran, sweet potatoes, peas, legumes, most fruit, and non-starch vegetables. Medium glycemic carbohydrates (56 to 69) are found in quick oats, brown rice, and whole wheat bread. Finally, high glycemic foods (70 to 100) are found in white bread, corn flakes, white potatoes, pretzels, rice cakes, and popcorn.

But most of us do not measure the glycemic index of our meals. There must be another part of this story, especially as it applies to women in menopause.

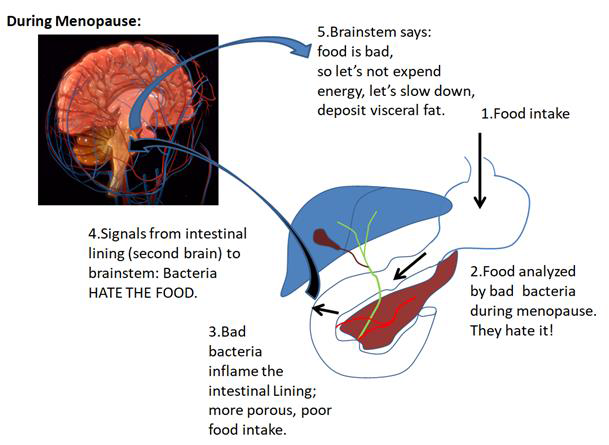

There is; it is the role of our intestine. Scientists recognize the power of the brain-gut axis as it relates to a number of autoimmune diseases that formerly were unrelated to the bowel. During the reproductive years, high levels of ovarian estradiol, a powerful anti-inflammatory hormone, bathe our intestine to maintain the integrity of our intestinal lining and a healthy and wide range of bacterial colonies. With the rapidly declining influence of estradiol during the menopause transition and into menopause, the bacterial colonies shrink in diversity, and the intestinal wall becomes more porous, sending signals to our brain. The response is to reduce energy expenditure, to slow down. The result is fat disposition. Worse, obesity leads to insulin resistance, the risk of diabetes, and cardiovascular events (Vieira, 2017).

What about hormone replacement therapy (HRT)? Most studies to date have relied on analysis of stool bacteria, a measure of colon bacterial activity. Animal studies have shown that HRT administrated to rats whose ovaries have been removed showed reduced absorption of glucose that was not seen in menopausal rats who were not given HRT (Singh, 1985). More recently, human studies have shown that the effect of hormones on the human gut microbiota (bacterial colonies) can significantly improve their bacterial diversity and reduce their role in autoimmune diseases (Lam, 2011; Ochoa-Reparaz, 2016; Vieira, 2017; and Becker, 2021).

The take home message: There is no simple solution for weight gain in later life. Clearly, simple carbohydrates are a path to more hunger, more eating, and more weight gain. But complex carbohydrates will always remain an essential component of our diet and a critical part of our body’s fuel. Complex carbohydrates may actually lead to decreased weight, not weight gain. And, “white” foods are too general a term and must be interpreted properly. But, age and hormone status in women explain why there is not a simple solution to this challenge.

James Woods | 4/14/2022