Is All Body Fat The Same?

Considerable progress has been made in understanding the role of obesity in healthcare. The old concept was that all fat was bad; that it was associated with hypertension and diabetes. Yet, some more recent studies report that certain overweight or obese individuals actually do not demonstrate these health risks. Now we are beginning to understand why.

Considerable progress has been made in understanding the role of obesity in healthcare. The old concept was that all fat was bad; that it was associated with hypertension and diabetes. Yet, some more recent studies report that certain overweight or obese individuals actually do not demonstrate these health risks. Now we are beginning to understand why.

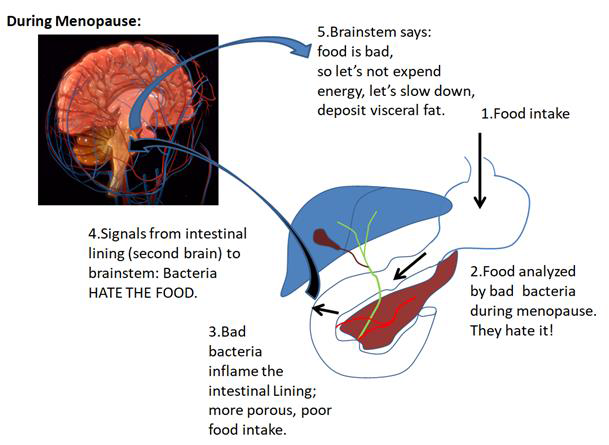

Body fat can be divided into subcutaneous fat and visceral fat. Subcutaneous fat is the fat that is deposited on our hips, buttock, arms, and belly. This fat does not seem to carry the health risks of visceral fat. Visceral fat, on the other hand, is fat that is deposited around our abdominal organs but also around our heart. Unlike subcutaneous fat, visceral fat cells are capable of generating many of the inflammatory proteins that attack our blood vessels and our heart. They also may play an important role in many other perimenopausal or menopausal conditions, such as memory loss, mood disorders, hot flashes, bone loss, and skin changes.

How do clinical scientists know where these fat deposits reside in our body? The gold standard for assessing body fat is derived from studies using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computerized tomography (CT scan). A close parallel has been found between these sophisticated and expensive methods and measuring hip or hip-to-waist measurements. Recently, ultrasound measurements of the distance from the back of the abdominal wall to the spine (or to the aorta in a modified protocol) has proved as effective as MRI or CT Scan for finding a correlation between these measurements and serum lipid determinations.

But how does the biology support the imaging? Using animal models, investigators have sampled subcutaneous fat and visceral fat and have demonstrated in the laboratory that only visceral fat cells generate the inflammatory proteins interleukin-1, interleukin 6, and Tumor Necrosis Factor (TNF), the same proteins that have been linked to most menopausal symptoms.

Do both types of fat increase in a similar way throughout life? No. Subcutaneous fat increases gradually as a product of aging and reduced activity. Visceral fat, on the other hand, rapidly increases in the three to five years prior to onset of menopause. Accompanying that increase in visceral fat are increases in carotid artery wall thickness and alterations in one’s lipid profile.

Is there any good news? Yes. Exercise, when begun in earnest, associated with diet control reduces visceral fat more quickly than subcutaneous fat in the early weeks of the program.

By James Woods, M.D.

Dr. Woods treats patients for menopause at the Hess/Woods Gynecology Practice.

Disclaimer: The information included on this site is for general educational purposes only. It is neither intended nor implied to be a substitute for or form of patient specific medical advice and cannot be used for clinical management of specific patients. Our responses to questions submitted are based solely on information provided by the submitting institution. No information has been obtained from any actual patient, and no physician‐patient relationship is intended or implied by our response. This site is for general information purposes only. Practitioners seeking guidance regarding the management of any actual patient should consult with another practitioner willing and able to provide patient specific advice. Our response should also not be relied upon for legal defense, and does not imply any agreement on our part to act in a legal defense capacity.

James Woods | 3/16/2015