I am 55 years old. My doctor tells me I have osteopenia. But I am also shrinking in height and now have pain in my buttocks and legs. Are these changes due to menopause or just my age?

Your Menopause Question: I am 55 years old. My doctor tells me I have osteopenia. But I am also shrinking in height and now have pain in my buttocks and legs. Are these changes due to menopause or just my age?

Our Response: The menopause years often are characterized by loss of bone density as well as reduction in one’s height. It would seem logical to link the two as contributing to your pain. Recent studies, however, suggest otherwise. A look at bone fragility first.

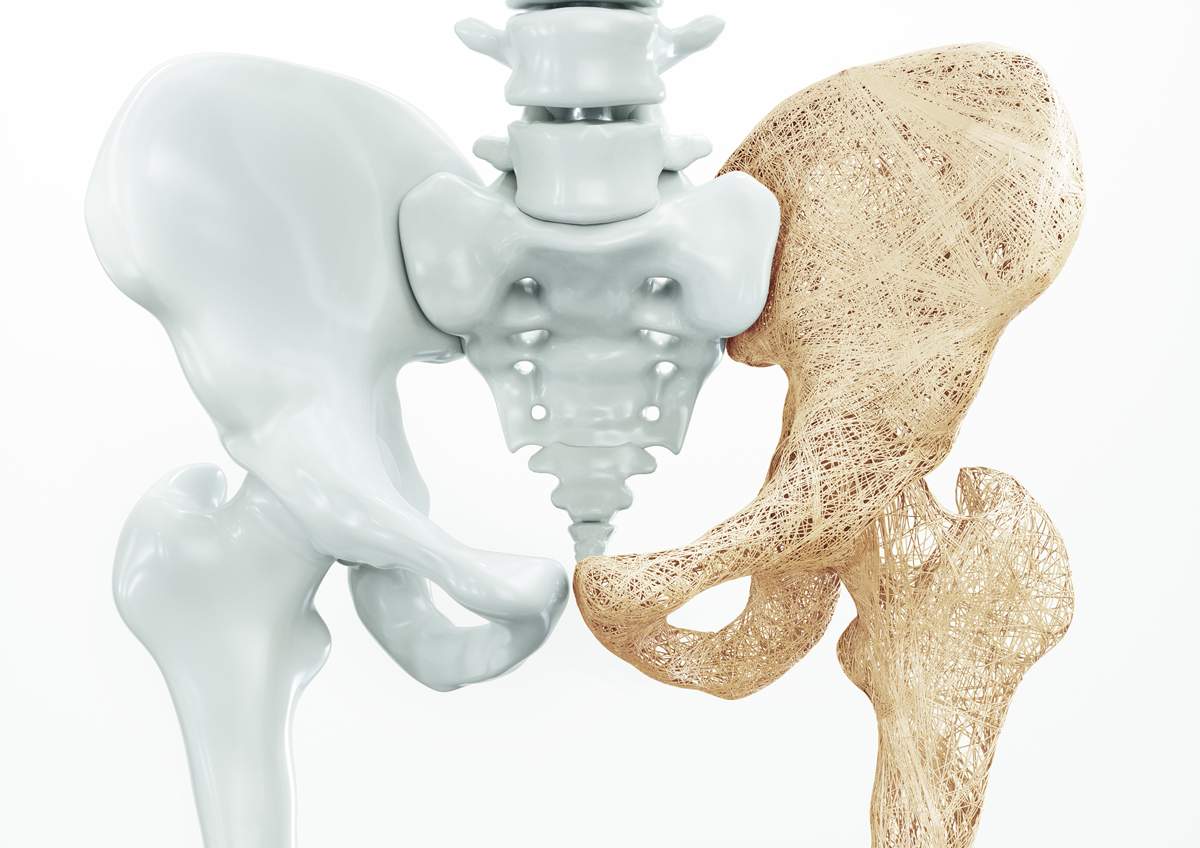

Our bones are a product of two types of cells. Osteoblasts produce bone and osteoclasts break down bone. Throughout our lifetime, we are constantly remodeling our bone as we make and break down our bones. During our reproductive years, the osteoblasts and osteoclasts are in sync. In menopause, with loss of estradiol with its anti-inflammatory properties, our bodies begins to circulate inflammatory proteins that stimulate the osteoclasts more so than the osteoblasts (Murray, 2012).

But, all bones are not equal. Our long bones are made up of hard, cortical bone, while our spine, ribs, and the neck of our femur (where the femur articulates with the pelvis) contain trabecular bone, which is more fragile. How is this measured?

Dual X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) has become the most widely used technique for assessing bone fragility (Blake, 2007). Employed initially in 1986 to study the density of our long bones, measurements in healthy, younger individuals established a value (referred to as a T score) of -1. T score values of -1 to -2.5 were assigned osteopenia, reduced bone density but not sufficient to treat. A T score of -2.5 (which represented 2.5 standard deviations from the mean of the younger group) or worse implied osteoporosis and consideration to treat. Because 25% of individuals who fracture their femur neck die in the first year, screening by DXA measurements was a major advance in preventive health maintenance (Metcalfe, 2008, and Schnell, 2010).

The DXA scan examines only the density of our bones. Other factors also affect bone health. In 2008, the DXA scan became incorporated into the FRAX score (Kanis, 2018). This newer analysis added age, family history, weight and height, smoking and alcohol consumption, or secondary osteoporosis. From this determination, a ten-year risk of a major osteoporosis fracture or hip fracture could be calculated.

If menopause with its inflammatory proteins puts bones at risk, would not imaging of the lower spine identify those experiencing buttock or leg pain and lead to surgical intervention? After all, low back pain affects two-thirds of the population sometime during their lifetime. And, disk degeneration and disk protrusion often are interpreted as the cause, leading to surgical interventions (Brinjiki, 2015). Perhaps a closer look at our spine.

Our spine is designed to support our body’s weight and is composed of vertebrae, each separated by a soft, collagen disk. The vertebrae are made up of two types of bone. The anterior aspect, which encircles our spinal cord is made of hard bone similar to that of our long bones. The posterior component of each vertebrae contains trabecular bone, which is more fragile but also more flexible. The collagenous disks separate the vertebrae and make up about one quarter of the vertebral column. What does this have to do with menopause?

In a perfect world, for normal balance, the canal that houses our spinal cord would be a plumb line from our occiput through C7 vertebrae, T12-L1, to the sacral promontory (Tome-Bermejo, 2017). More importantly for our body’s function, nerves exiting from our spinal cord service the rest of our body. Any compression or injury to our spine can present as distant nerve pain. So pain in our buttocks or legs can originate from compression of nerves to that part of the body as they exit from the spinal canal. Or, they can come from ligament or muscle injury.

But what does this have to do with shrinking and low back pain if everyone is getting a DXA scan sometime in menopause? Perhaps it is the changing composition of our spine as we age. Or, that the ratio of cortical bone (hard bone) to trabecular bone (more fragile bone) in various bones differs.

Recent data indicate that a substantial number of individuals with abnormal lower back imaging are asymptomatic. In a systematic review of 33 articles examining the prevalence of spinal degeneration by imaging (magnetic resonance imaging or computed tomography) in asymptomatic individuals, disk degeneration was documented in 37% of 20 year olds and up to 96% in 80 year olds. Disk protrusion increased from 29% in those 20 years of age to 43% in those 80 years of age (Brinjkji, 2015).

What can one conclude from these studies? It appears that spinal degeneration along with shortened posture can cause buttocks or hip pain from compromised nerves as they enter the spine. However, findings on imaging also can be from normal aging and not necessarily associated with the described pain. Thus, when menopausal patients are presenting to their physicians complaining of height loss and distal pain, appropriate imaging and a thorough discussion are needed and not simply the assumption that surgery will resolve all symptoms (Brinjikji, 2015).

James Woods | 6/4/2021